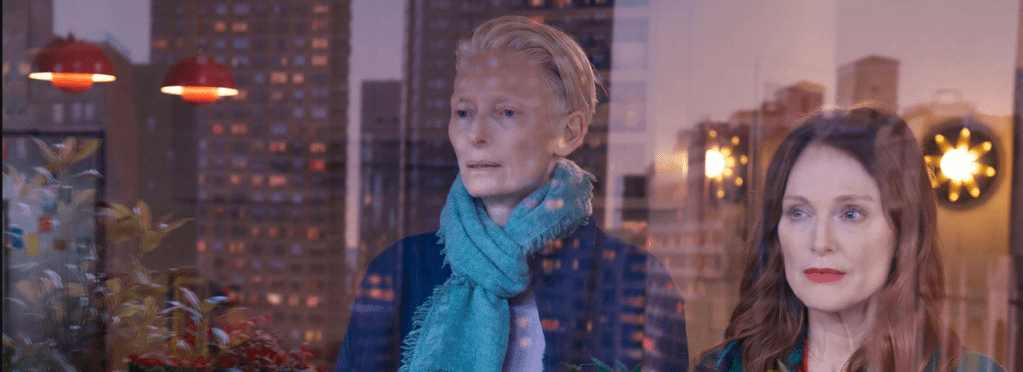

When Ingrid (Julieanne Moore) learns of her friend Martha’s (Tilda Swinton) cancer diagnosis, she wastes no time in visiting her. It’s been years since their last reunion, but they greet each other warmly in Martha’s private room in a New York hospital. Martha is gaunt and white but glowing (in a way only Swinton can manage!). Her hospital room is warm, looking like the inside of an afternoon, full of flowers, and a beautiful view of the city scape is visible. ‘You seem in good spirits,’ Ingrid says during their conversation, and the gentle naivety of her comment deflates Martha somewhat. Martha confesses that she almost didn’t want to be treated at all when she first found out, she was ‘ready to go!’ But Ingrid remains optimistic. And so, begins the delicate evolution of the pair’s conversations about and feelings for Martha’s impending death. Moore is stunningly grounded. What starts as Ingrid’s love and concern for her friend quickly becomes a stern confidence and dedication to their friendship. She does this so elegantly, and the transformation is fast, almost unwavering. When, after another failed attempt of beating the cancer with treatment, Martha asks Ingrid if she would help her die, Ingrid is understandably stunned and emotional but attentive to her friend’s request. The conversation ends with Ingrid saying she ‘has to think about it.’ By the time she’s downstairs getting into a taxi, she has made up her mind.

Although the audience may glean some closure from Martha’s dignified death, the film is far from celebratory. We feel, as does Martha probably, that her dying is a kind of burden, not just on her, but on those around her, namely Ingrid. Despite this, director Pedro Almodóvar relishes in using elaborate offerings of fresh fruit to adorn certain significant settings. When Ingrid is first invited to Martha’s apartment, she seems to have an endless supply of grapes, apples, peaches. And when the pair arrive at the house in which Martha is to die, they have a similarly generous quantity. Even at the end of the film when Martha’s daughter, Michelle (also played by Swinton) arrives to see her dead mother, the first thing she is offered by Ingrid, and eats, is fruit. Unlike Elena Ferrante’s novel and subsequent film, The lost daughter, where the living character is haunted by quickly decaying fruit, it’s significant that the visual of fruit in The room next door appears to be used more optimistically, reminding us of vitality in a film that is so heavily about death. Though aware of her demise, Martha chooses to hold on to, and then let go of, life as she feels is appropriate. Coupled with fruit is the recurring use of windows, and their corresponding views from which Martha watches the world around her. Martha’s apartment, like her hospital room, offers a similarly stunning view of the cityscape, although nothing compares to the 360-degree view of the forest from the secluded house in which Martha says her final farewell to the world. The breeze, the birds, the pink snow: all features of the landscape which continue to make their way into the rooms via open windows and doors.

Both Martha and Ingrid are single throughout their time together, and I wonder if this allows them to develop a unique kind of intimacy. If even just one of them were in a relationship, maybe the space between them would not have been so close — Martha may have had someone to help her die without calling on a friend, or Ingrid may have been talked out of her decision to help. The film emphasises the friendship between the two, but still leaves space for possible and plausible readings of other aspects of their relationship. The small gestures of reassurance through touch, language and eye contact means that the friends share a gaze that is almost equal to, if not more intense than, lovers. Ingrid’s signature red gloss lipstick, part of Almodóvar’s intense colour palette, is adopted by Martha a few times in the film, most notably when she readies herself for death by dressing up in bright, penetrating colours. Whatever has been said between the two remains between them only, a pact, a secret, a promise. The life which Ingrid embodies so beautifully, transfers so movingly to Martha on her deathbed out by the pool, in the elements which have always intrigued and wondered her.

The speed at which Ingrid and Martha reconnect, seems radical, but not impossible. The two women who had worked together many years ago and who haven’t spoken in years have a fierce and fast transformation, which can only be attributed to Martha’s illness and subsequent request. The deeply intimate information which Martha reveals to Ingrid is shocking because, unlike two friends who may have known for ages and would have probably known these details more intimately, Ingrid is largely unfamiliar with Martha’s past, her experience with motherhood, the father of her daughter. It’s also important to remember that by the time Martha’s desperate attempt to ask Ingrid for help comes around, she has already been abandoned and rejected by ‘others’ who had been — and we can only guess here — too afraid, or too judgemental, or too busy, or too self-centred…. And yet, while Ingrid is afraid, she does not lack courage. A writer herself, it could be understood that she has an ability to empathise with experiences that are not her own, in a way that is deeply sophisticated. Ingrid doesn’t accept the invitation to help Martha die purely because the two are friends, she does it because it is the moral thing to do.

Martha’s careful plan to die while Ingrid is ‘the room next door’ never eventuates. She envisioned her readiness for death had always involved companionship — as she reminds Ingrid, even when she worked as a war correspondent, they always had someone with them when going into dangerous or unknown territory. And yet, when Martha does die, she manages to transcend her wish by deciding to take her final pill when Ingrid is out of the house. In her final letter to Ingrid, she notes that it was somehow a comfort to her, knowing that she was out in the world, living her life, doing her own thing. The magic of accompaniment is that it can take different forms and through her sheer commitment to ‘being there’, Ingrid helps Martha realise that although she must die alone, perhaps she doesn’t need to face her death alone.

Martha is dying, but she is also immensely privileged. She has the means to access comfort for her final moments. It’s complicated, and in no way straightforward, but her wit, capital and friendship with Ingrid are the only way in which she has been able to make it happen. After Martha’s death Ingrid is, as predicted, heavily interrogated by the police who suspect her complicity. Thanks to her own pragmatism, initiative and foresight, Ingrid ensures she has a lawyer is on hand to support Ingrid, who only after this intervention is dismissed by police, a move that even Martha didn’t think to prepare her for. There is no mistaking how deep the ideologies behind death and its circumstances run in this part of the world. Had Ingrid been anything other than astute and well connected, we would have witnessed an entirely different drama.

The film eloquently addresses dying with dignity at a time we would like to go And yes, we find ourselves contemplating death, perhaps of those we know and have already gone, or those who have had a close encounter with it, or maybe even our own. But in order to fully comprehend the gravity of the entire film, we cannot leave the cinema without meditating on the unique nature of Martha and Ingrid’s friendship: Martha’s frank request for help, and Ingrid’s steadfast loyalty, the unique and solemn bond between them. Death itself, although central to the narrative, is not the tragedy, rather it is the strain of responsibility which Ingrid bears as the sole support. When, in the leadup to Martha’s death, Ingrid meets a friend with whom to disclose her situation, she is advised admirably ‘You’re the only person I know who doesn’t make others guilty about their suffering.’ And it’s true, Ingrid has suffered. Not the cancer or the subsequent gruelling battle, but the sole brunt of keeping her and Martha’s sanity intact while they navigate the terrain of euthanasia in a country where the death penalty is widely allowed across the country, but it’s illegal for a person to determine the quality of their death and, by extension, the people they choose to support them through it.

Almodóvar’s film is stark in its messaging, poetic in its delivery and brutal but beautiful in its storytelling. It’s difficult to leave this film without meditating on death, if not that of others, then of our own. In the film’s final moments, Michelle meets with Ingrid at the house where Martha has died. Played too by Swinton, the appearance of Michelle is almost funny, who dons the same pale complexion, but whose face is framed by an auburn crop instead of her mother’s short white hair. Taking a bite of the fruit which Ingrid has offered, she discards the green top of a strawberry on the kitchen counter, listening earnestly to her mother’s closest confidante. With Swinton refusing (symbolically) to leave the film, embodying now her daughter, it isn’t that Martha is still ‘present’ — her death is in some ways the most certain thing about the film. Instead, Swinton’s return to the screen feels like a forceful reminder that we are engaged in a piece of fiction. The Martha we came to know was never really there, and the bodily vehicle through which Martha’s story has been told will continue now to tell the stories of others. And it’s a reality that the characters must come to terms with, in the same way that audiences will come to terms with death in their own lives. Once someone is gone, our way of remembering them is through recollection and story, always told through and by others. If, after death, we have no control of how our life is portrayed, what a privilege then for an individual to determine their final moments.